During 2020, several crowdfunding platforms had already failed in Estonia, but the loudest scandal in Latvia was about Envestio, as its roots could be traced to Latvian entrepreneurs. Surnames related to Latvian political circles, and contacts even at the level of the Prime Minister’s Office, now appear on an even larger platform registered in Estonia, but operating in Latvia, founded and managed by Latvians – Crowdestor, where the amount of lost money could be many times larger than the infamous Envestio, the newspaper Diena reported.

Is it another Latvian financial pyramid scheme?

During 2020, several crowdfunding platforms had already failed in Estonia, but the loudest scandal in Latvia was about Envestio, as its roots could be traced to Latvian entrepreneurs. Surnames related to Latvian political circles, and contacts even at the level of the Prime Minister’s Office, now appear on an even larger platform registered in Estonia, but operating in Latvia, founded and managed by Latvians – Crowdestor, where the amount of lost money could be many times larger than the infamous Envestio, the newspaper Diena reported.

Risk or deliberate deception?

The crowdfunding platforms established in Estonia are dying one after the other, almost in order, by the year of establishment. The life cycle is about three years, and an analysis of their operation begs the question: are they not essentially new digitally modernized Ponzi schemes?

Experience to date has shown that crowdfunding platforms are failing one after another. From the examples of already extinct platforms, it can be seen that the cause of the failure is either fraud or the fact that sooner or later the platform displays clearly unrealistic ideas with fantastic interest, which ultimately turns out to come from the platform creators’ imagination. Namely, the commitment to pay more than the company in a particular industry can earn in the most successful development scenario is deception, although there is always a legal possibility to say that the investors themselves have been reckless.

Envestio example

Last year, more than 2,000 investors in Estonia wanted to recover several million euros from the crowd financing platform Envestio through the court. The Estonian newspaper Postimees pointed to the connection with Latvia, which has been widely described in various media. Investors joined up and made one of the largest deposits in the history of Estonian state courts – 200 thousand euros – to prevent Envestio bankruptcy proceedings from dwindling, “to prevent the transfer of assets from companies used in the scheme”, said Denis Piskunov, partner of the law firm Magnusson representing the defrauded investors.

Envestio was initially registered in Latvia in 2014, but the crowd financing platform started operating in 2017. In 2018, Envestio SI was registered in Estonia by Antons Kaļetins.

Investors were promised very good interest rates for various projects in different countries.

Piskunov called the whole thing the Ponzi scheme. More than 2,000 investors from Spain, Germany and Italy approached the Estonian police to start a lawsuit against Envestio. The total amount of customer claims reached 15 million euros. As most of the projects were imaginary, it turned out that only a few tens of thousands of euros could be seized in bank accounts in Latvia and Malta. According to the lawyer, a large part of the money was withdrawn in cash. Special emphasis is placed on the fact that approximately one-third of Envestio projects were related to Latvia and in some cases were also real business or the companies had assets used as collateral. Namely, there were so-called advertising projects, where in some cases borrowers did not even realize that they were used for advertising the platform.

The bankruptcy of Envestio is being heard by an Estonian court, and it is likely that these companies will be looked at in the course of the proceedings with various claims, which will also reveal who was the fraudster and who was the victim of the scheme.

What has already been found out in the course of the investigation – some of the investment projects were fabrications – fake projects.

The true beneficiary

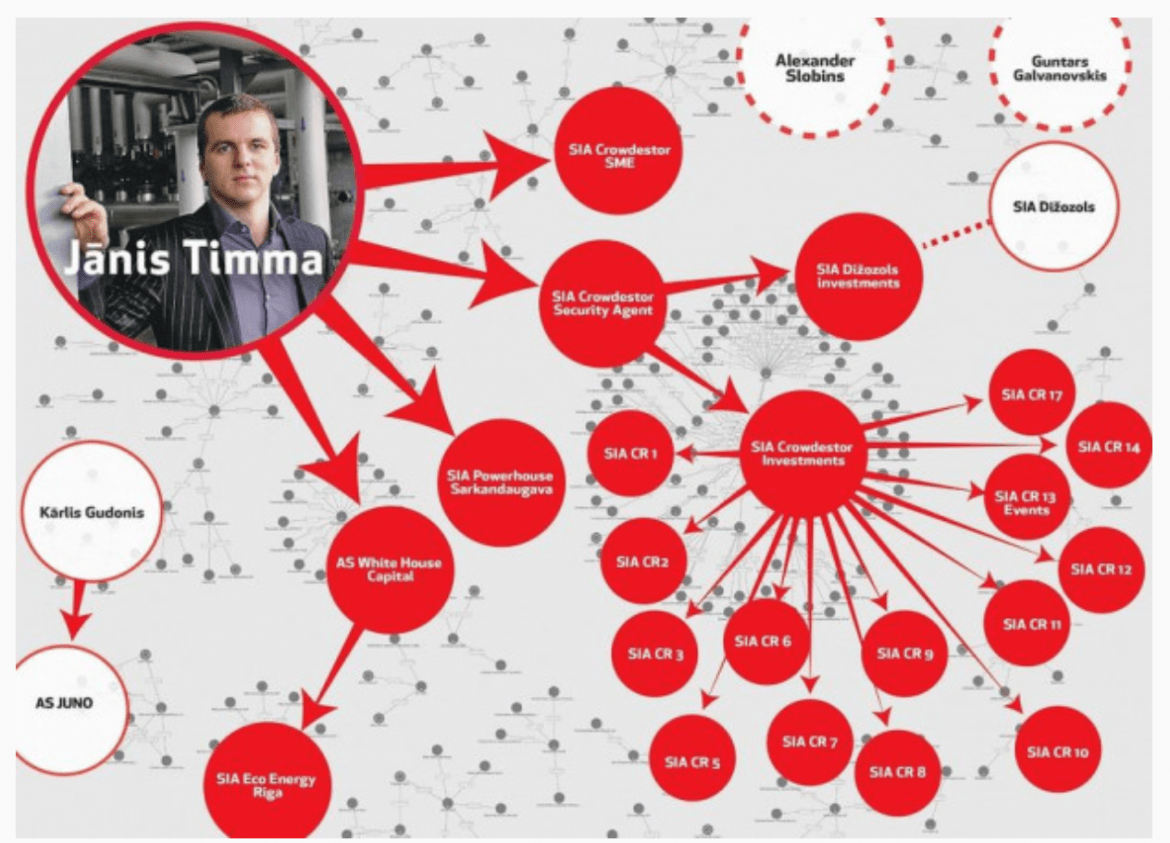

The Crowdestor platform was also founded in Estonia, and Crowdestor is also actually a Latvian creation, and the funds there are mainly attracted to Latvian business, which at first glance might please us. What causes unpleasant questions is the scheme itself. Namely, there is one true beneficiary in the center of this corporate web – Jānis Timma, who is surrounded by dozens of connections with other people and companies. To avoid misunderstandings – he is not the basketball player.

Jānis Timma is both the manager of the platform and the true beneficiary of a large number of companies that attract money to these companies through the supposedly independent crowdfunding platform. For example, SIA Powerhouse Sarkandaugava, SIA Dzirnavu apartamenti, and SIA Dižozols Investments. Jānis Timma is also the real beneficiary of a number of SIAs with the names CR1, CR2, CR3 … CR17, which are companies for accumulating the money raised on the platform and indirectly owned by either SIA Crowdestor Security Agent, SIA Crowdestor Investments, or others that also owned by J. Timma.

The information available in Lursoft about the true beneficiary scheme of Jānis Timma looks like a huge spider web with the weaver in the center.

Web of borrowers

When analyzing Crowdestor’s investment attraction projects, the names of the borrowers must be read carefully, as relatives, friends and acquaintances are involved in the transactions that form a single network of borrowers, and in not all cases Timma attracts funds directly to his companies. For example, at SIA Dižozols Investments he is the true beneficiary of only 40%, and the loans lead to a completely different network.

Another example is the summer 2020 project, in which a transport company sought money on the Crowdestor platform to refinance loans. The carrier has 19 trucks. An annual rate of 17% is promised, to be paid monthly. The transportation company is 60% owned by Raimonds Timma, who is the father of the aforementioned Jānis.

Jānis Timma himself, as the executive director of the Crowdestor platform, talks about SIA Powerhouse Sarkandaugava on the platform. In 2020, the company wanted to borrow 950 thousand euros at a rate of 21% for two years. Lenders are asked to do so, saying that money is needed to buy wood chips and refinance the debt of the SIA shareholders. Considering that the prices of wood chips were devastatingly low last year and the money for the sold energy is not delayed for more than 30 days, it must be understood that J. Timma, the sole owner of the SIA, asks investors to lend money to give it to one large lender.

Exotic projects for the reckless

Exotic projects outside the European Union are typical of Envestio and can generally serve as a shadow of suspicion in other cases as well, as information on practical activities somewhere in South Africa or East Asia is very difficult to verify in person.

One of Crowdestor’s projects is to collect fertilizer for cotton plantations in Africa. From mid-January 2020, funding was collected for fertilizing cotton plantations at an interest rate of 21% per annum. The total value of the contract is 4.5 million euros, the platform attracts up to 1.9 million euros. The loan term is three months.

“At the moment, we have submitted a request to the police for non-return of 1.6 million euros,” J. Timma admitted in a telephone conversation about this project and stressed that the borrower has deceived the platform. Attempting to agree on a broader interview covering all topics, J. Timma was initially open to talks, setting March 15 as a possible date for the talks after receiving questions, but then suddenly stopped responding. When trying to arrange an interview, we had the same feeling that one of the investors told us about – deception and stalling.

There are serious grounds for concern and stalling is unacceptable. The total amount of attracted capital is approximately 47 million euros, which was confirmed by J. Timma himself in a telephone conversation. 16.9 million euros has been refunded, which means that EUR 30.1 million is currently in circulation, which is twice as much as the lawyers contracted by the lenders are trying to recover in the case of Envestio. According to the information available to the Diena, 157 Crowdestor projects could have problems with refunds, and that is why we wanted to meet with J. Timma to ask him some questions. Unfortunately, J. Timma did not find the time to answer them. The questions are still valid, and we are posting in this article the exact same questions that were sent to the true beneficiary of Crowdestor.

Crowdestor’s investors are mostly foreigners, regular people from Denmark or Germany, who invest between 1,000 and 5,000 euros.

Given the serious concerns that Crowdestor, like Envestio, threatens the image of Latvia as a land to invest in, we still hope to receive answers to questions.

Human connection

The Estonian police, in co-operation with Latvian law enforcement, have not yet established a link between the various platforms, but suspicions of such a link could arise.

The LTV program De facto, researching the Envestio scheme in Latvia, names Eduards Slobins, who works in the field of logistics, and a few other surnames that are well-known in the business environment. “3.5 million euros were received by companies owned by logistics entrepreneur Eduards Slobins – SRR, WTS, Zelta jumts, Transports nomai,” De facto reported earlier this year.

Slobins is the link between Envestio, which is being liquidated, and the Crowdestor platform, which was created a few years ago and where funds are received by another Slobins, a relative of the aforementioned E. Slobins. For law enforcement, from a legal point of view, it is a different natural person, but from a human point of view – it is a person who had the opportunity to obtain and learn the entire fraud scheme in a particular business model from a relative.

Questions to Jānis Timma, the true beneficiary of the Crowdestor platform, to which J. Timma did not find the time to provide answers.

1. When was the Crowdestor crowdfunding platform established? What was the main goal or the first idea, why is it needed? Why in Estonia? Did you have experience in this type of business yourself?

2. Some of the companies to which financing was attracted are your own. Why raise so much money if the company is liquid? Why not use bank financing for green technologies, such as Altum funds, if we are talking specifically about SIA Powerhouse Riga?

3. CR1 SIA, CR2 SIA, etc…., CR17 SIA, are companies founded in the period from the summer of 2019 to the spring of 2020, in a very short time! What are these companies? Why was such a number needed in such a short time?

4. What is the loan portfolio of the Crowdestor platform in large numbers, how much money went through, how much have investors earned, how many projects were unprofitable or sold at a loss?

5. Not all projects can be successful at such high borrowing rates as a whole because there are failures even at lower rates, is there a mechanism to protect investors? How does it work?

6. You have a specific example with non-refunded money. You said by phone that you had asked the police to investigate. What’s next? Can investors hope to get their money back? How would this happen? Is the platform going against the non-payer and trying to obtain collateral, or should the defrauded people do that?

7. When was it discovered that the money would not be paid back? Namely, when did the problems start, when were the lenders informed, when was the application submitted to the police?

8. You own several companies that borrow money through the platform. Are the companies where you are the real beneficiary cost-effective now, are they in operation, are they already profitable, do they have tax arrears? When do customers receive information about the situation? Namely, yearly reports are a very slow method. Are customers informed faster and who audits the information provided? Or is it a matter of trust, if you invest, then you trust what the borrower says? Are borrowers’ reports for 3 months really always available, as promised to customers?

9. What would happen if, as the owner of the Crowdestor platform, you had to pursue refunds against yourself as one of the borrowers. From a purely technical point of view – is everything so simple here? Or, for example, against one of your relatives? Father or other relatives?

10. The internal market for platform promissory notes depends on the information provided. For example, the stock market has the concept of raising alarms internally, which causes panic in the stock market, for which severe penalties are imposed. Your platform is also similar to a stock exchange and information about the status of companies, or its lack, or even a statement in a lender’s chat can cause panic and the sale of discounted promissory notes. What is this internal market for promissory notes, how much is being sold? How many sell with interest, how many are discounted, what is the percentage on average, if there is such information?

11. Do you or the companies you represent participate in the promissory notes market on your own Crowdestor platform? How many promissory notes have you bought if you are willing to disclose this?

12. Do you see an ethical contradiction in the business model, because in theory there is a possibility that you can buy your own debt for the money lent to you and cause a sale, because you are responsible for disseminating information? Namely, although everything is legal, there is an ethical objection, it does not look quite neat from the point of view of the structure of the system!

13. The Crowdestor platform accumulates money, sometimes for a week, sometimes for a month, depending on the activity of investors and the target amount, until the start of the project. Is that so? Where are these semi-accumulated funds, do they earn money, where is the additional money spent?

14. Questions on specific examples:

a) Raimonds Timma borrows money to refinance a Transport Company with a high interest rate. It is known that 2020 was a difficult year for the Transport sector and, in general, the Transport sector does not have high profit margins. Why did you decide that this is the right way to refinance, since the risk that the measure may fail is high? Has the deal been closed, how successful is it?

b) The cotton fertilizer saga, which ended with the entrepreneur not giving you 1.6 million euros, looked like a very dubious project from the start. At least a third of the amount must be paid for delivery to the other side of the world. Were you sure that the risks here were low enough?

c) The same entrepreneur from Liepaja is closely connected with electric kart manufacturers and has cooperated with them, which I know from interviews in Dienas Bizness last year. Is there a possibility that the practice of non-refunding will continue?

d) We already talked by phone about the SPA and hotel project on the other side of the world, which seemed fictional to me, because I really don’t have the opportunity to go there and see for myself. You said by phone that this tourism business will be incredibly successful during Covid. Can you elaborate a little? How can it become successful, if tourism is practically banned?

Source: newspaper Diena

Lasītāju viedokļi